Vilém Flusser, “Ontogenese wiederholt Phylogenese,” 165-168 in Vom Subject zum Projekt: Menschwerdung, Stefan Bollmann, ed, Bensheim: Bollmann Verlag, 1994. My translation.

When you reach an age that may euphemistically be called maturity, you may decide to write a good, fair, exact, in short a definitive text, a summation. With a probability bordering on certainty, you will then stumble in writing this text as if over your own feet. You will pursue it nevertheless, pushing questions about what you are writing, how you are writing, into the background. For what you are writing about is obvious: Ontogeny repeats phylogeny.

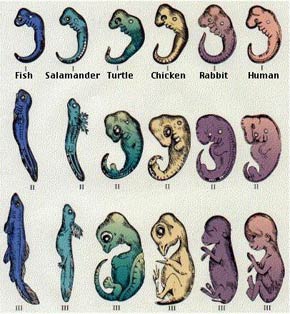

The beauty of the repetition is that it is so inexact. We’ll shed some light on the imprecision with examples from three different levels of life. When the sperm fertilized the egg, an amoeba-like entity appeared. In examining an amoeba, one experiences something of the fertilized egg, and in examining a fertilized egg, one experiences something of an amoeba. But luckily there is not and has never been an amoeba that could be compared to a fertilized egg. It is lucky, for if there was such camparability, people who oppose abortion would have to oppose all water purification plants. So the person who is writing the good, fair, exact text must deal with the ambiguous parallels between amoebae and human embryos.

Second example: The newborn baby behaves in a way that is closely related to that of the first sort of human being. When we watch the baby’s kicking, we can see something of the behaviour of so-called primordial man. Since we unfortunately cannot see the behaviour of primordial man for ourselves, we must restrict ourselves, as some gestalt psychologists and behaviourists do, to watching chimpanzees. There never was a primordial man who behaved like a baby, and no baby is a primitive of species homo. The good, fair and exact book to be written will have to contend with the ambiguous parallels between Homo erectus and our baby.

Third example: At puberty, we all wrote romantic poems, whether in praise of a girl we loved, or in defence of a political or religious ideal. We all rhymed and chanted and formalised as if living in the 18th century. But there has never been a romantic poet who wrote like a 20th-century teenager, and never a teenager who, even one who had, against the odds, read Byron or Goethe, them wrote like. Nevertheless, romantic literature enhances our understanding of 20th-century puberty, and we can enhance our own understanding of romantic literature by considering what we wrote at the time of our own puberty (should we be able to master our embarrassment).

Is this, then, the content of the book to be written? Amoebae as human eggs, early hominids as babies, the romantic poet as a teenager between the world wars? If it is to be a summa, this, and nothing else, must be its content. Its title, too, is prescribed, namely, Becoming Human: Becoming human in the sense of ontogenesis, so that the writer tries to turn from an amoeba, past an early hominid, into a romantic poet, shortly before reaching still higher and turning to dust. Becoming human in the sense of phylogenesis, as our specie has tried to get beyond the biological, the animal, and the genomic, shortly before failing in the ashes of Auschwitz, Hiroshima and others.

But this two-tracked title “Becoming Human” demands subtitles: it refers as much to the individual as to the specie, and it means the development of the individual exactly because it means the development of the specie. It must become a triptych. The first part must be called “for the time being,” because it is about somehow getting a glimpse of what is ephemeral in everything that is present to us. The first part has to fix what changes. The second part must be called “momentary,” for it is about somehow catching a glimpse of what is ephemeral in what our eyes see. The second part has to find insights in sights. The third part must be called “traceless” because it is about getting a glimpse the ephemeral in everything we leave behind. The third part must recover what has vanished.

All that comes to the surface when you have decided, in maturity, to total things up. And this is the good thing in the whole story: The text is to be written in maturity, which is to say at the end of the second millennium CE. Of course after the second millennium comes a third, but what does that matter to us, who have sucked our juices from this millennium? For us, everything ends with this millennium. This text will be written in maturity, at the end of Western civilisation. Of course after the Western will come another civilisation, perhaps an immaterial or postmodern one. But what does it matter to us, whose value are based on the West? For us, everything ends with the West. This text will be written in maturity, roughly between 70 and 80 years. Of course the world does not end with the death of the writer, but what do we mean by “of course” here? The great thing about this ambiguity is that in maturity, ontogenesis and phylogenesis blend. With this life, a way of being ends, and with this way of being, a life ends, In writing his history, the last Mohican writes the history of the Mohican race.

That is a kind of preface to a Mohican history. Who could be interested? Post Mohicans? Perhaps there is actually someone who would read it, but first someone must be found who would publish it. And with that, we see what motivates the rumbling, stumbling intention to write a good, beautiful correct book. Verba volant[spoken words fly away]. They are present, momentary, traceless. But scripta manent [written words remain]. They pause before they blow away.