A Photographer on Mars

Opportunity Rover was a very engaging robot. It “lived” on Mars for nearly 15 years, gathering and transmitting data back to earth; it “died” or, as NASA put it, completed its mission on 13 February 2019. In terms of its work, Opportunity was a field geologist, quite literally superhuman in its expertise, reliability, tenacity, and selfless commitment to a project larger than itself. In terms of its achievements, it was a great explorer, at the level of Magellan or Humboldt or Cook, making entirely new spaces “imaginable” for human beings who would never actually see those spaces for themselves. In terms of its relationships with people, however, Opportunity emerged as warm, fuzzy and innocent, more like a precocious child than the rigid, implacable machine it really was.

Its “last words” achieved instant celebrity: “My power is low and it’s getting dark” certainly tugged at many human heartstrings around the world in the final weeks. The sentence was a playful translation of cold numerical data, readings of battery charge and light levels transmitted by Opportunity toward the end of 2018. The translator, Jacob Margolis, a journalist and, crucially, human being, wrote it (“translated” was his term) with no intention of misleading anyone. One might better say that he engaged a well-established tendency among readers and viewers of Opportunity’s news from Mars, a habit of investing the reporter with a state of mind or, as some would once have put it, a condition of the soul.

Although it sent vast quantities of numerical data about materials and surfaces and distances and temperatures and wind speeds and entered into sustained relationships with earth-based scientists and engineers, it probably wasn’t the quantity or clarity or even the novelty of the information that made the rover seem so human. It was the photographs. Opportunity resembled anybody who picks up a camera and looks through the viewfinder, adopting the position of a “functionary,” to use a term of Vilém Flusser’s. For an image formed by light that has passed through a camera lens and registered on a surface conforms to a stable, consistent industrial standard. It just isn’t much like human memory, which is, by contrast, is notoriously unpredictable — compressing time, eliding distinctions between senses, changing every time it is accessed. But we willingly, almost automatically accept the constraints, adjusting eyes, hands, consciousness to the needs of the device. With that, we plug ourselves in to a huge network of people and machines, embracing camera designers, advertisers, critics, publishers, exhibition spaces and more, all linked together in massive, continuous feedback loops. From the moment of picking up the camera we get a sense of what needs to be done to get a “good” photograph, what’s of interest, how it “should” be framed. Images made according to the rules sustain and heighten the sense of mutual need. We need, or think we need the device in order to remember our own past, and the industry unquestionably needs us to sustain itself. For human beings, this mesh of people and machines – Flusser called it an apparatus — represents both gain and loss. To the extent we control it, insisting that it serve our needs and desires, we move toward the most exciting, playful, genuinely humane society the world has ever known; to the extent we allow it to control us, continually accepting “default” settings, settling for what is expected, often against our better judgment, we erode our own freedom, and with it our unique capacity to create new information. We erode our humanity.

Flusser singled out photography as not only as the first, but also a particularly clear instance of the way the apparatus works. But it is only one. By now, machines are integrated into virtually every aspect of our activity, automating human decisions and standardizing human behaviour. Flusser was clear, even at the time he was first describing it in the mid-1980s, that there was no longer any possibility whatsoever of resisting the apparatus entirely, and so refusing the role of functionary. We have become too dependent on apparatuses for our life support. But by resisting the “pull” of the apparatus toward predictability and conformity, there is always the possibility of inducing it to make something new. It can be done, he wrote, in three different ways: by interacting with the apparatus in an unprecedented or unanticipated way, by actually changing the apparatus in terms of its capacities or limitations, or by “translating” between apparatuses.

Opportunity the photogenic robot, the mechanism that scampered about the surface of Mars for so long and was finally interred in Martian dust, never created anything. It took images constantly, including many selfies. It shared them all and kept making more, whether there had been any response or not. When it moved to a new place it did the same thing. It didn’t edit, categorize or provide commentary. It did what it was programmed to do. By zooming out to the point of seeing Opportunity as an apparatus (in this case we can call it a “mission”), however, an entirely different picture emerges. The mission coordinated the very different gestures of thousands of people – in science and engineering, design, manufacturing, finance, politics and marketing – many of whom needed to defy the apparatuses of their respective fields and frameworks to meet the new challenges the project presented. And the apparatus produced vast amounts of genuinely new information. It “imagined” a whole planet! It is surely what Flusser meant when he suggested that apparatuses could facilitate a fantastically creative society – if human beings, by resisting some aspects of their functionary roles, require the apparatus to create.

In his recent book The Creativity Code (London: 4th Estate, 2019) the mathematician Marcus de Sautoy asks whether computers are or can be creative. The underlying assumption is that the two are in some kind of competition. Most of the examples either compare human beings with machines or actually pit one against the other, providing dramatic tension, but also leaving everyone wondering just what “creativity” is. One especially illustrious example is the well-publicized Go match between AlphaGo, the brainchild of the gifted programmer Denis Hassabis (in cooperation with Google), and Lee Sedol, an acknowledged global champion. In a round of 5 games in March, 2016, AlphaGo “won” — according to the rules of Go and the terms of the match. But that hardly does the story justice. It is like a tale of ancient champion warfare, with plenty of suspense, twists and turns. It is enough to convince us that the relationship between humanity and artificial intelligence just can’t be represented by a contest. AlphaGo made one move in particular, in game two, move 37, that astonished everyone – programmers, fans, and Sedol himself — although AlphaGo did not react at all. “Beautiful, beautiful,” one observer said — and it seemed to many to be evidence of creativity. Sedol’s “retort,” as de Sautoy put it, was move 78 of game 4, a decision that took him an exceptional length of time to make, and that eventually surprised everyone, apparently AlphaGo included (38).

The match between Lee Sedol and AlphaGo ostensibly pitted a human being against a machine. But it took humans to recognize and appreciate that move 37 was completely new, humans to grasp the implications, and humans to incorporate the new information into their own engagement with the game. It took humans to design and program AlphaGo as well, to teach it the rules of Go and – the really brilliant recent innovation in AI, credited to Hassabis – to enable it to learn from its own experience. The match was really between a human and an apparatus, that is, between a human being without a direct live link to artificial memory, and an artificial memory co-ordinating the thinking and memory of a select, specialised group of human beings.

In the chapter entitled “Playing” in the book Into the Universe of Technical Images(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), Flusser pursues a description of what creativity would look like in the universe of technical images (the telematic society of the very near future — effectively our own). Two people are playing chess, and enjoying the challenge, not expecting any particular surprises. Then the gameplay takes them to a configuration neither has seen before. They look up from the game and begin to share their surprise, consider the implications. They reflect on the game as such and their own playing of it. Both gain something, and the question of who won or lost fades to insignificance.

The match between AlphGo and Lee Sedol is widely acknowledged not only to have astonished and enlightened its audience, but to have changed — enlarged and enhanced — the game of Go for all players from now on. That’s creative. It has nothing to do with who won or lost. Absorbed in the question of whether one or the other opponent was “creative” or not, we will miss the spark that quite clearly jumped between them.

In the context of Flusser’s thought, “creative” becomes a synonym for human. Machines are not creative by definition, and in a situation that makes it seem that way, chechez l’homme. Humans in cooperation with machines — apparatuses — can be either fantastically creative or plodding robotic shells. Apparatuses can and do encourage –- some might say “force” — their users to be reductive, lazy, crude, repetitive and anything else that is not creative — in a word, inhuman. In everyday life with apparatuses any one individual can and in fact is likely to feel overwhelmed. It does not need to be like that, however. AlphaGo, to choose a single example, treated its user with scrupulous respect and incorporated what it learned from the exchange into its own memory.

It is possible to behave exactly as the Opportunity Rover landing module did, like a robot, relying entirely on the apparatus to make decisions and store the results, declining to exert any critical human judgment at any point. But we can also decide to participate, engage with the apparatus. At the opposite end of the spectrum, a well-loved photographer such as Martin Parr, once he’s broadly framed a topic based on his own attractions, interests, curiosity — may shoot many, many images without knowing exactly whether or how they relate to the topic at hand. One might say he lets the apparatus help him break the ground. But to earn the honour of being one of Parr’s, an image must meet his own thoroughly human criteria. Parr controls the apparatus, gives it reign at points, reigns it in at other points, coaxes or forces it to project a unique, unprecedented potential Englishness, something that had been there for a long time, but never quite seen by anyone before. Readily recognizing something new, viewers invariably nod in recognition, laugh outright, or look again.

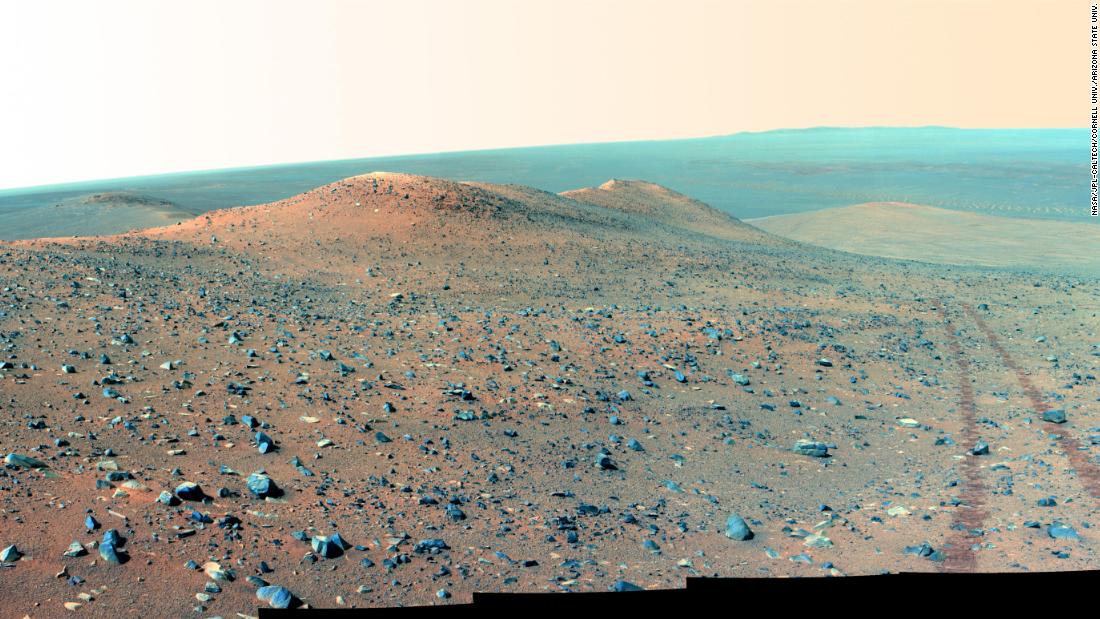

We don’t ask whether Opportunity Rover’s photographs are “good shots,” well-composed, lit, focussed, etc. Most of them measure up well to such criteria, just because the apparatus’s camera was programmed to make conventional decisions, and the equipment is technically superb. But the strangeness of the landscapes, the curious shadows and tracks, the composites of multiple single images making up single comprehensible forms, the tiny numbers often found at the edges add up to something — add up to a particular look. They are absolutely new, and so perhaps unlikely to be very likeable just yet (Flusser defines “creating” simply as generating new information). Far from aligning themselves readily with any kind of photographic art, in any case, they engage viewers’ curiosity – perhaps about Mars, perhaps about the apparatus that supported the mission, and perhaps about photography. For these images are particularly successful in exposing the tap roots of the medium, its foundation in physics, chemistry and rigorous rational thinking, its systematic, implacable isolation of “seeing” from any natural human tendency toward simultaneous multi-sensual perception.

Strange and estranging, the images from Mars are the products of a robot, an inhuman functionary attached to an exceptionally large, closely-coordinated and well-focussed apparatus. The robot’s endearing habit of taking travel pictures surely at least enhanced human beings’ sense of identification or empathy, for most of us would expect to do exactly the same thing on a journey to a very distant and alien place. In generating so much empathy with a travel photographer who is not and never was human, the mission exposed something very old about photography, about its stark, radical difference — possibly even antagonism — to human perception or memory. The Rover may also have given us a gratifying glimpse of something we quietly or unconsciously desire, hardly daring to hope for its actual realisation, namely a functioning mesh of humans and machines – an apparatus – with recognizably human values.