Heartfield and Photography

The celebrated German photomontage artist John Heartfield (né Helmut Herzfeld, 1891-1968), had an astonishing gift for finding specific photographs and reconfiguring them as news in a world of his invention — a world in which newspapers reported the devastating effects of greed, ignorance, and callous indifference on the part of government and industry. Many such photographs really were “found,” and could be made legible in the Heartfield’s world by means of a caption.

The work is called “Forced Supplier of Human Material”. The caption below reads “Keep going! The nation needs soldiers and unemployed people.”

Many more needed to be rescaled and collaged with others, then matched to either a found or invented caption.

Occasionally, though, Heartfield imagined a photograph taken by someone in the invented world, someone who had seen a Christmas tree turn into a swastika, for example, had snapped a photo.

♫ To the tune of the Christmas carol “O Tannenbaum”: Oh Christmas tree/ in Germany/ How crooked are your branches.

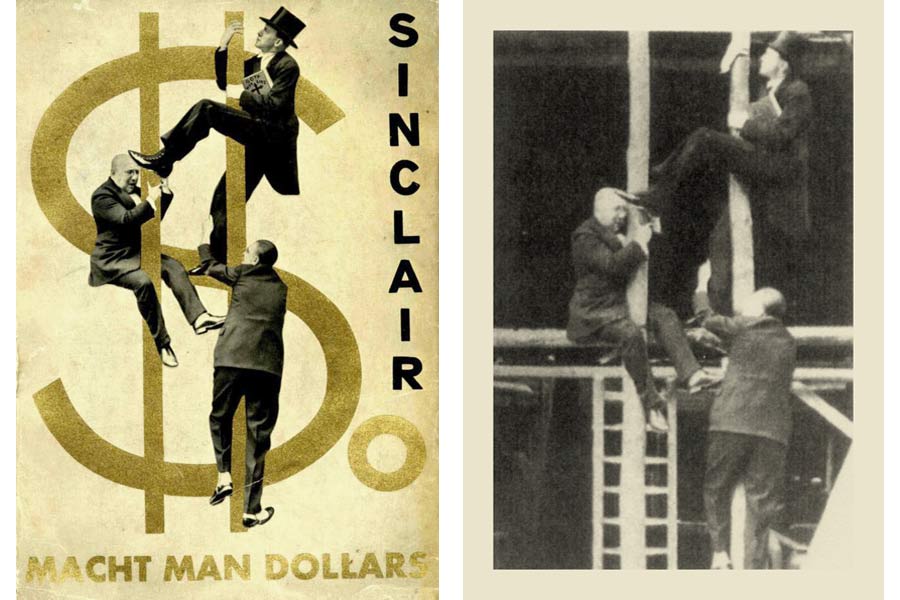

Another example, reproduced above, was a dust cover for “So macht man Dollars,” the German translation of Sinclair Lewis’s book Mountain City, from 1930. In such cases Heartfield hired an assistant. Although he would supervise the staging very closely, he never took such photographs himself.

Heartfield’s brother Wieland Herzfeld explained this as Communist solidarity. The Herzfeld brothers were confirmed Communists, as was the newspaper that published the photomontages. Wieland effectively invented the version of John Heartfield that is now famous, insisting on a wholly political motivation and all but missing the artist — the man who built a whole world from photographs and words. Wieland insisted that John hired photographers because there were comrades — committed Communist photographers who needed work. I doubt that this was the reason.

I credit Heartfield with a both a respect for most readers’ faith in photographs as representations of reality, and a nearly evangelistic mission to introduce challenges, to enable readers/viewers to see into, past, through photographs. The photomontages contain photographs that lie, distort, omit, mislead as well as astonish, celebrate and commend: they are never neutral. Because he did not want the message construed as “personal” and himself dismissed as an artist expressing himself, he insisted that the staging of his imagined photographs be collaborative. Heartfield’s work explicitly and very consistently rejects the idea of photography as personal expression (still, possibly, the fastest, most superficial take on photography as art). He made sure that every photograph he used had engaged at least one mind and body, one consciousness other than his own.