Deaf Republic: Book Review

Ilya Kaminsky, Deaf Republic, London: Faber and Faber, 2019.

You might wonder, as I did, whether I was reading a fable, a myth, a folktale, a parable, or something else, something different. Of course it is something different — or perhaps it would be better to say it is all of these things, and none, exactly. It is poetry, which I’m sure includes them all. Still, it seems worth asking the question now, in retrospect, in order to get at what doesn’t “fit” any available category, how it all becomes so difficult to pinpoint in time and space: it seems like a very old in some ways, but not in others; it’s addressed to everyone and yet adroitly “speaks” to specific readers; it’s anchored in a some kind of folk or fairy tale tradition — a village, a street, a square, “once upon a time,” and still, events somehow resonate everywhere — across a nation, across the world. It’s too long to be a “fable,” too short to be a myth.

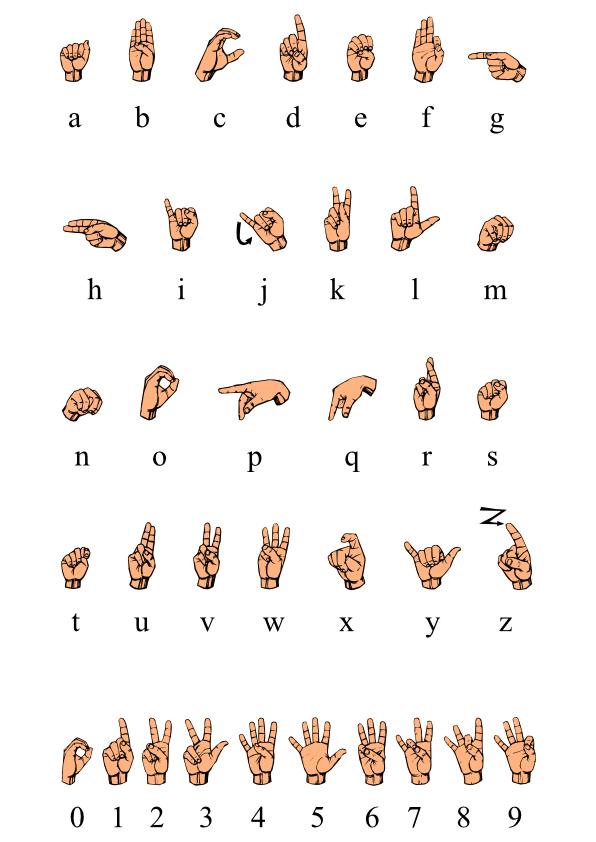

I’ve rarely felt so clearly that a story is about the reader. Events hinge on a confrontation between villagers and a group of soldiers that seems resident for the time being, but belongs in some vague way to some larger, presumably national military organization. The locals instantly reveal themselves to be be loveable, warm, human, and the soldiers stiffen into instruments of violence. They shoot and kill a deaf boy for no perceptible reason. Spontaneously, the villagers defend themselves by claiming to be deaf: they cannot hear what the soldiers say to them, cannot do what they are asked to do. At the same time, they invent a silent sign language in order to communicate with one another. And here is where a reader slides into an unprecedented position. Readers really can’t hear. They go on reading the story, in one sense, from the position of a villager feigning deafness, although they can “see” at least some of the villagers’ messages to one another. They know about the senseless murder and retribution, the agony of a family ripped apart; in other respects, readers are in the position of soldiers, who can see the pain they have caused, the loss, and feel they can do nothing about it. The forces of human community, the creative energy of language confront some expectation or acceptance of what we are likely to call reality. It could be a definition of poetry.