Nomads don’t need Archives

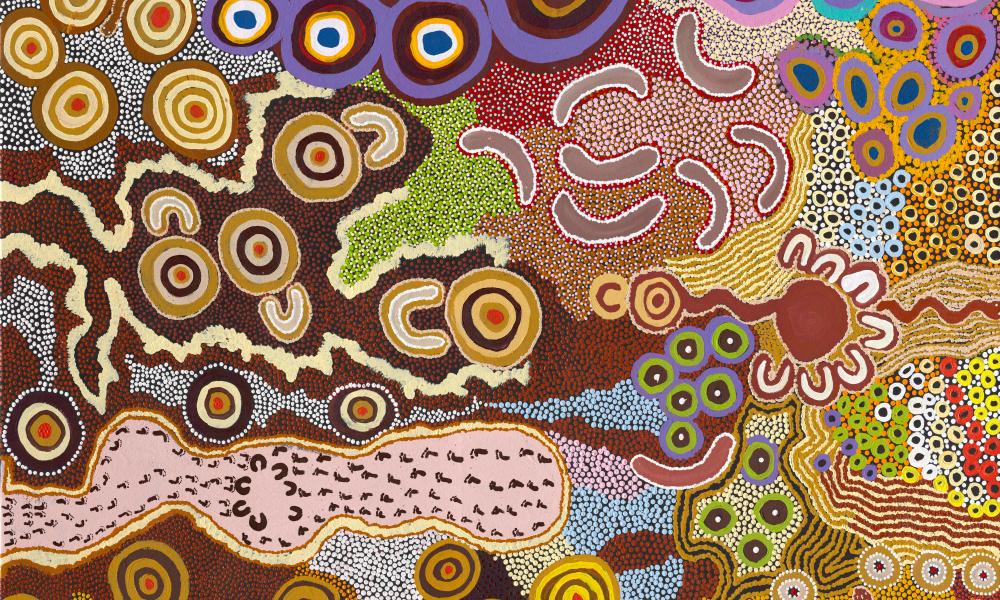

Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters is an exhibition organized in Australia, now travelling to Europe and the US. It looks a lot like an exhibition of paintings, and it would command close attention and respect seen as expressions of individual sensibilities and perceptions. But that is not what it is. Many of the canvases were painted by groups, and many voices are heard on the videos, all with the specific intention of building up an archive.

On entering the exhibition, visitors “meet” the elders, six life-sized projections on video screens, each speaking quietly, gesturing enthusiastically, smiling, sometimes pointing, explaining that Jukurrpa — songlines or “the dreaming” — is in danger of being lost, and that this exhibition is meant to preserve it. “The dreaming” is the most usual English equivalent for Jukurrpa, or Tsukurpa. The word changes according to the language spoken in the land where the narrative takes place. For the dreaming binds a human being to a specific place, meshes sound — spoken or sung — with land, embodied human perception with specific topography, weather, light, plants, animals, dangers, obligations and prohibitions. It involves a narrative, a tale of beings travelling through the land, participating in dramatic confrontations, creating the world as they go. There is no fixed beginning or end: the events, the creation, has happened, is happening now and will go on happening forever.

The Seven Sisters is one particularly long and well-known Jukurrpa — “story” is perhaps the most flexible equivalent. In the framework of this exhibition, the story extends through three distinct regions and involves four different language groups. Everywhere, the same wild tale prevails: a rude, sexually-obsessed man in pursuit of a group of seven women — sisters, although perhaps in a variety of senses. The man changes shape, even name. He can detach his penis and send it ahead to do his bidding, even underground if that seems to be advantageous for him under the circumstances. Yurla, or Wati Nyiri — again depending on the language — is violent, manipulative — effectively a clever and relentless rapist. The sisters evade him again and again, dismissive, taunting, even more manipulative than he is sometimes. Eventually, however, he changes himself into a snake and the sisters eat him without knowing the identity of the meat: they die but are transformed into the constellation Pleiades; the man seems — it’s not very clear — to turn into Orion. Is this all in the past or present? How can such a tale be foundational, binding a society together, tying everyday events in everyday lives to all of time and space? How do thousands of small confrontations, attacks, chases, near-misses, integrate land to people? Are we looking back on a state of mind that has passed, or are we in the present? How does the story begin?

These are the questions of someone whose oral experience is very limited — largely to immediate family and friends — and whose larger culture has relied on written texts, maps, equations, laws, moveable and reproducible images, for centuries. It’s a kind of consciousness that expects beginnings and ends, explanations, a proper “history” as supported by archival sources — in a word, writing. Although it is not stated directly, the exhibition marks a loss of oral culture and more, an acceptance of this loss: it announces a shift from a culture that stores its critical memory in human bodies to one that relies on “external” storage, writing, painting — and more recently, photography and video. Painting, specifically, works as external storage when and if it is moveable, on canvases. The exhibition also contains photographic records of elaborate cave paintings, images that require the participation of a human body to “read,” — the paintings of an oral culture. The makers and viewers of this exhibition share a hope, if not a conviction, that writing and images and digital files can reconstruct, regenerate the Jukurrpa.

People all over the world have experienced a transition away from oral culture as tragic and irreparable loss, the indigenous people of the Americas being among the most prominent examples. The change has usually entailed the most horrible violence, suppression and inhumanity, concluding more or less completely with the oral people becoming literate, their minds engaged with writing and all the many technologies that rest on it. At this point, the aborigines of the Western desert are no longer nomads, no longer wholly oral people whose past and future is integrated with their bodies and the land, people who do not want or need archives. The elders themselves do remember — the stories, laws and language, and above all the land, sky, plants and animals. But they no longer believe their children will.