Dylan as Listener: The Philosophy of Modern Song. Book Review

Bob Dylan, The Philosophy Modern Song, London: Simon and Schuster UK, 2022.

It’s technically a book, of course, but you need to listen to it as much as read it. It’s organised as notes to 66 selected songs — the selection and ordering lying at the heart of the matter. In fact Philosophy challenges so many of the categories and boundaries most of us associate with books that you can start to admire it for that reason alone. We all know, for example, that “philosophy” is written. Because it’s in the title, we probably go on to assume that this book is Dylan’s philosophy. I don’t think so. But the mistake, if there’s been any, has been ours. This philosophy is sung. We readers have become listeners, and — perhaps more remarkably — so has the author. He treats songs as distinct world views, and writes in the interests of expanding, appreciating the songs’ philosophies, the particular times and places they create, the moral and aesthetic realities they share.

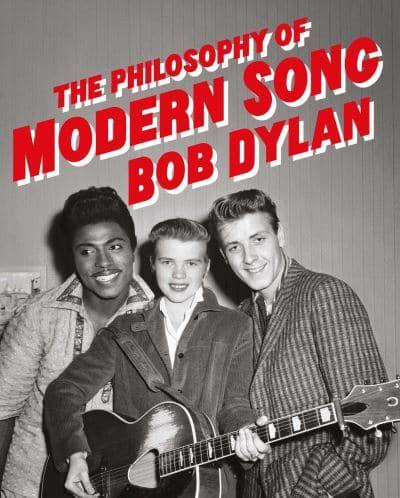

The book is richly illustrated, too, but the relationships between illustration and text are no more conventional than the one between reader and writer. They add things — asides, quirky details, or broad context. Often, they’re surprising: suddenly, there may be an illuminated manuscript, a product advert, or a very well-known painting (e.g., Cézanne). An illustration may add something about the time and place the song projects, a mood, a contemporary enthusiasm, an ideal; sometimes it broadens a metaphor in a particular lyric into a timeless human fear or hope. The song Beyond the Sea, for example, (written by Charles Trenet; popularised by Bobby Darin) includes a literally fantastic line engraving (read: 19th-century journalism) of sailors in small boats threatened by whales, swirling helplessly in a high sea.

Bob Dylan is a writer, and a celebrated one at that. The Nobel Prize was for song writing, however, and this is different. There had to be a finite number of songs, and the notes had to be in some sort of order because this IS a book; But it’s up a to reader to construct a basis for the selection, and that almost inevitably happens in comparison to what that reader imagines she might have chosen in similar circumstances. And it’s impossible not to sense Dylan in the choices, which spiral around American songs of a time he names “modern” — 20th century. Past. The order is neither chronological nor alphabetical nor anything else reassuringly familiar. I doubt that either the choices or the order were anything like haphazard, however, and I’ll take the last sentence of the text — and last of the book — as evidence. The topic is music:

…it is of a time but also timeless…music is built in time as surely as a sculptor and welder works in physical space. Music transcends time by living within it… by living it again and again.

I don’t feel as though I’ve finished reading this book, perhaps because it doesn’t feel exactly finished itself. I expect to return to it as to a unique reference book, a project that may have its roots somewhere in the idea of a memoir, but that has turned out to be a new kind of book, and an account of a way any one of us might really listen to music.