Speaking of Matter: Review of Q.E.D.

Feynman, Richard P, Q.E.D.: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter, Princeton, 1985

I loved many things about this book, but above all the moments when Feynman let own joy, unabashed wonder at the physical world shine through. A close second would be the care, skill, the empathy, imagination and respect he brought to the project of sharing this with us. He assumes we’re intelligent, curious people who want to learn more about the patterns that particle physicists study. He assumes we want to understand. He does too. So when he tells us — as he does a number of times — that we don’t understand, he quickly adds that it’s OK, because physicists don’t either. No one does. And that’s OK too, because it’s so much fun to learn more about it.

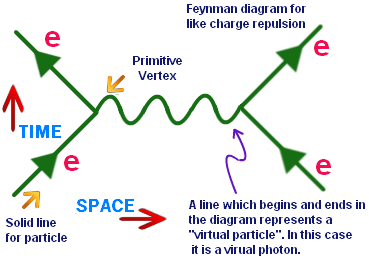

The book then faces the challenge of describing what happens, how particles behave. Nothing ever seems very definite or predictable — there are probabilities and possibilities and boundaries. Feynman invented a means of “talking” about these patterns using small drawings representing particles in motion. They’re like tiny characters in a newly-invented system of writing (definitely not alphabetic!). He draws a photon as a very small, undulating line, for example, calls it an “amplitude” and indicates the distance it has travelled by the length of the line (time as the second, usually vertical axis). The drawings have a few familiar features, in other words, like the x and y axes in geometry. But they’re different. And they’re very entertaining! They’re like tiny stories, and it’s probably best to just try to understand the story…a possible fate for some particular particle, without trying to imagine the speed or quantity of these particles at the same time, because it quickly becomes overwhelming.

At the beginning of the book, he’s seems to be walking us up to and into the huge daunting structure called Physics, always alert for the features likely to seem threatening, overwhelming. He assures us, for example, that he’ll be telling us not about the whole of physics, which includes gravitational forces and nuclear forces, but rather he’s just going to show us his own area, quantum electrodynamics (Q.E.D), “the interaction between light and matter, or the interaction of light and electrons” (p. 4). It’s easy to say.

He supposes we might be wondering how physicists are different from us, for example — because they really seem to be! He boils it down to what they learn in all their years of education. This turns out to be something like a language — not unlike the “tricks” we all learned in school for multiplication and division of large numbers, but far more complex and comprehensive. The language enables physicists to communicate with one another with speed and precision, and opens new dimensions, possibilities — a new universe, one might say.

Niels Bohr, one of few central figure who established the principles of quantum physics in the early years of the twentieth century, repeatedly insisted that the new way of approaching matter would have to be stated “in the language of classical physics”. Bohr himself was notoriously awkward with language. Controversy surrounds many of his written statements and no one feels very certain about what he meant by this one either. And still, the phrase resonates. Notoriously articulate, by contrast, Richard Feynman, in this book, seems to have addressed this very issue, namely the issue of a language in which to speak about matter, now, when new discoveries seem steadily to undermine earlier assumptions and the very idea of language seems compromised. Without diminishing the complexity, without talking down to those of us who can’t “speak” higher mathematics, Feynman has here, in words and drawings, suggested that a translation might be possible.

In keeping with a spirit of wonder and joy about science in general and physics in particular, Feynman seems, at some level, to regard his readers as potential recruits, to suppose that any of us could be “hooked,” fascinated enough to learn the “tricks,” the mathematical language, become a physicist. You get the feeling he would have liked that.