The Man Made of Words (N. Scott Momaday): Book Review

The book is a collection of short pieces that are between or about or in addition to fiction, but not themselves fiction, the kind of book I always hope will illuminate the nuts and bolts of the writer. They were written over several decades in all kinds of times and places, and I was not surprised to find the reading a little lumpy. The middle section seemed to border on travel-writing, and although it never failed to be absorbing and insightful, it was sometimes difficult to hear the voice of the man made of words, the man who introduces himself with the very brief, very elegant story that opens the book. It is about a Kiowa arrowhead-maker, a story remembered from his father’s many retellings. It would be a disservice to paraphrase — by all means read it for yourself! It establishes key features of Momaday’s understanding of what a writer is and does: a conviction that the possibilities of language are infinite and mysterious, and it is with them, in them, that we all build our respective worlds.

The storyteller’s place within the context of language must include both a geographical and mythic frame of reference. Within that frame of reference is the freedom of infinite possibility. The place of infinite possibility is where the storyteller belongs (112).

He goes on to underscore the profound differences between cultures that rely on oral speech and those grounded on written documents, repeatedly alluding to the beauty and power of spoken, sung, chanted words and making readers aware of how easily they can be obscured, lost, forgotten. Momaday was a member of the Kiowa tribe; he appreciated the music of Kiowa speech and knew many words of the language, but did not claim to have been fluent. Of course he was profoundly literate (Ph.D. in English literature at Stanford), and there is no going back, not to anything like “pure” orality, at least. But neither is there any sense of an unbridgeable gulf between “us” and “them”. Rather he addresses readers who can “hear”, in his written words, profound respect for the very different position of words and silences among primarily oral people, and for the critical importance of those words for any real comprehension of America and its people.

In one passage I found particularly memorable, he aligns himself with the emigrants:

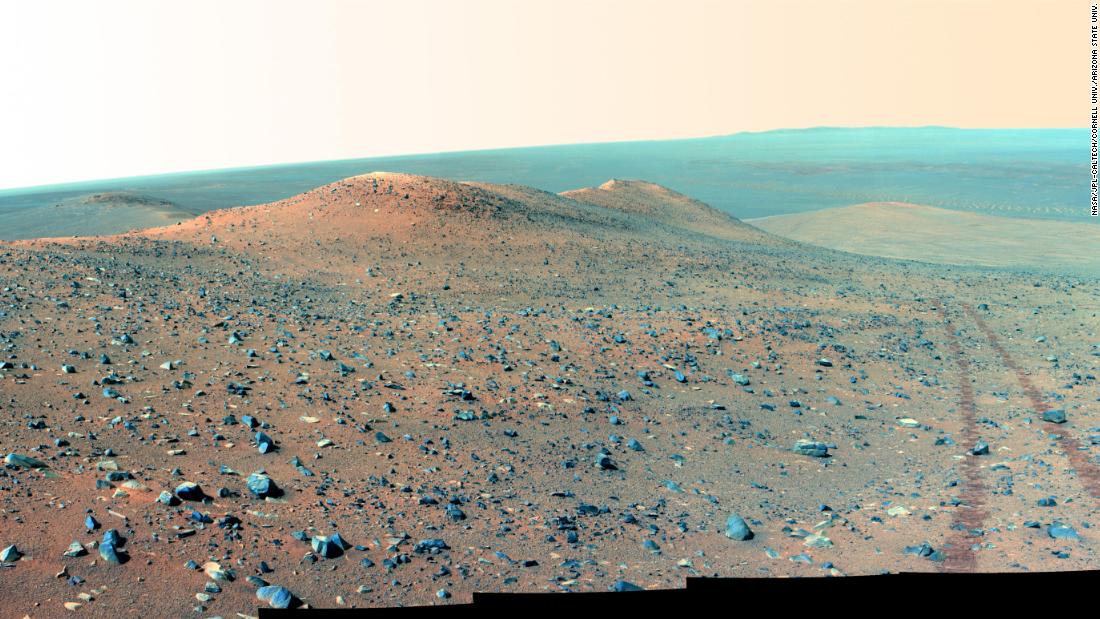

One function of the American imagination is to reduce the American landscape to size, to fit that great expanse into the confinement of the emigrant mind. We photograph ourselves on the rim of Monument Valley or against the wall of the Tetons, and we become our own frame of reference. As long as we can transform the landscape to accommodate our fragile presence, we can be saved. As long as we can see ourselves on the picture plane, we cannot be lost (97).

It’s as if he’s cast himself as one of “them” for whom a snapshot suffices, although at the same time he’s the writer of a text that insists on the irony of a flat, shiny, surface in relation to the often overwhelming forces and expanses of the American landscape.

One of the short pieces toward the end of the book, describing a return to Bighorn Medicine Circle in Wyoming, becomes an occasion for a reflection on sacred places and a meditation on something fundamentally human about experiencing them. Momaday first saw the monument when he was retracing the path of the Kiowas’ migration from the Yellowstone area of Montana toward what is now Oklahoma, an event that occurred so long ago as to be unspecifiable among people whose history is told from one generation to the next. Although at this point he’s become someone different from the earlier self who visited, he still finds the place and its effect on him profoundly mysterious. He goes with a friend, a native man. At first, they have some difficulty locating the right road. About the time they solve that problem, a stranger drives up in a battered old car. He turns out to be a quiet, studious-looking young man, a Swiss visitor, who is looking for the same monument. They go together, but look, listen and walk quietly, independently among the stones. When they are about to go their separate ways, the young visitor extracts a small camping stove, water, kettle, cups, tea and biscuits in his car and makes tea for all three. Momaday remarks on the unspoken desire for some ritual to mark an encounter with others in a sacred place, a desire felt by someone from another generation and another continent, as well as by those with more immediate connections. The three, he writes, whether or do not they ever have any further contact, will always remember that place and one another.