Translating and Transposing

It’s heartening to know that the celebrated translator Lydia Davis is open, in fact enthusiastic and curious about new, or inventive moves between levels and contexts and forms of language. She has taken a text from the English of one time and place to the English of another for example, or from memoir to long poem — still within English (pp. 109-212 in Lydia Davis, Essays Two, Penguin 2021).

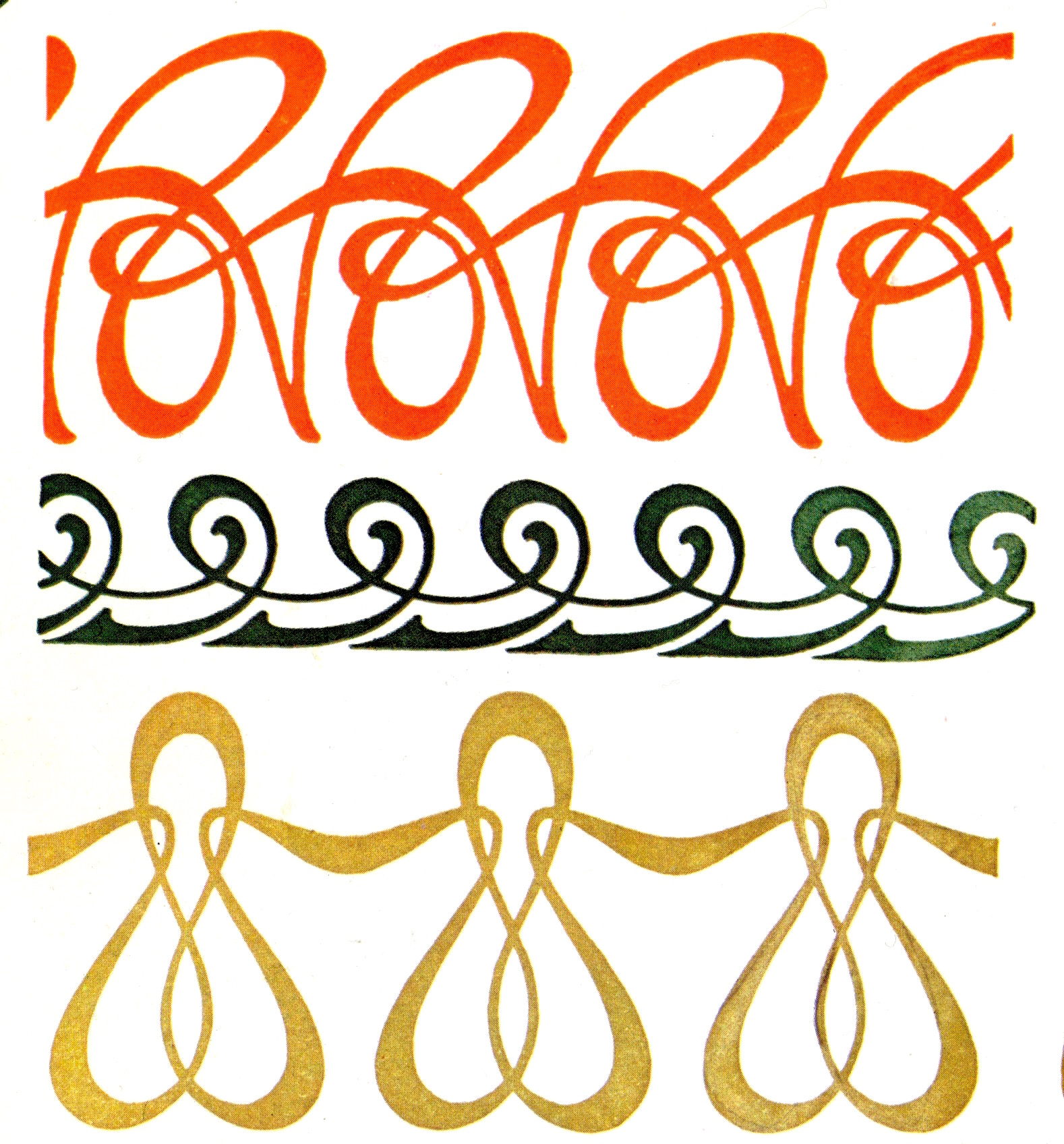

I myself translated a wonderful book a few years ago, a careful, systematic argument about the philosophy of perception. I’d like to be able to talk about it with my friends, both because we share a serious interest in perception, and because I keep thinking about the author’s contention, namely that perception produces us, rather than the other way around, some six years after the translation was published. And yet the small group of my friends — Anglophone artists and writers who are really interested in perception — can’t read it. I don’t think the reason is language, exactly — it’s good, clear writing, and a fluent translation. Both author and publisher were perfectly happy with my translation. But my friends and I aren’t professional philosophers. We have no particular stake in the fortunes of philosophy as such, or of phenomenology understood to be one possible way of philosophising. I think about translating again, differently, for different readers. Or not exactly re-translating, but re-framing, repositioning. I like the idea of transposing the book, as you might transpose a song into a different key, so more people could play or sing it, because I think it matters. If we really are the results, rather than the masters of what we see, hear, taste, smell, etc., doesn’t it change everything?