The Spell of the Sensuous: Book Review

This book seems like “mine,” in a sense few ever turn out to be. That’s because it recognizes the difference between spoken and written language. It’s a subject of very long-term interest to me. Hardly anyone seems to even notice, to say nothing of lending this difference any importance. The Spell of the Sensuous does. That alone would have been a relief. But it gets much better.

Abram does not think that reading and writing are everywhere and always wonderful. In contrast to the almost ubiquitous belief that anyone who doesn’t read or write should learn (and surely will want to), this book focusses on the very, very high price that must be paid when reading skill is acquired. If you read, when you read, you must narrow your “natural” perception drastically, pay attention to marks on a surface in a way that makes it impossible for you to attend to the full spectrum of perception humans have at their disposal — a rich array of coordinated sensitivities evolved to enable humans to live in a world of rocks, waters, plants and animals. In narrowing their perception down to an intersection between vision and hearing, the requirement for reading, they effectively cut themselves off from the rich relationships that human beings are equipped to have with the natural world — a cut that can be, and very often is, perpetuated indefinitely.

Perhaps it sounds simple. Perhaps it can be stated simply. But it isn’t simple, and Abram knows it well enough. He begins with a lively description of his own heightened experience of sound and colour and smell and touch as a result of having spent several months among people living in Bali, largely reliant on spoken language — without signs or engines or sirens and video images. On returning to his home in a large, busy American city, much of this perception abruptly disappears. He shares his sense loss.

By beginning this way, he derails a reader’s probable assumption that a society that does not read and write will be “past,” and one that does read and write will be “present” or future. We are addressing difference in the present. The book goes on describe a historical framework for the invention, development and spread of writing; it emphasizes the critical importance of the Greek alphabet in underpinning the vast, global changes we can, in retrospect, associate with literacy, followed by a spectacular expansion in technologies that depend on reading and writing for their precision, consistency and spread. That much is, in itself, is fairly well-established, although Abram is admirably clear and concise in his account.

But it is rare for an author to ask readers to be aware of themselves as readers. Abram continually anticipates– and simultaneously resists — readers’ tendency to assume that “we” are more highly developed, “better” than non-readers. We readers “know” before we even pick up the book, for example, that writing was invented a long time ago and that it has a complex history. People who rely on speech to share information don’t “know” this in the same way. Knowledge lodged in human memory is not so abstract or absolute; nor can there be “history” in the sense we may think of it among people for whom time is not uniform or unidirectional, and past events may never have ended at all.

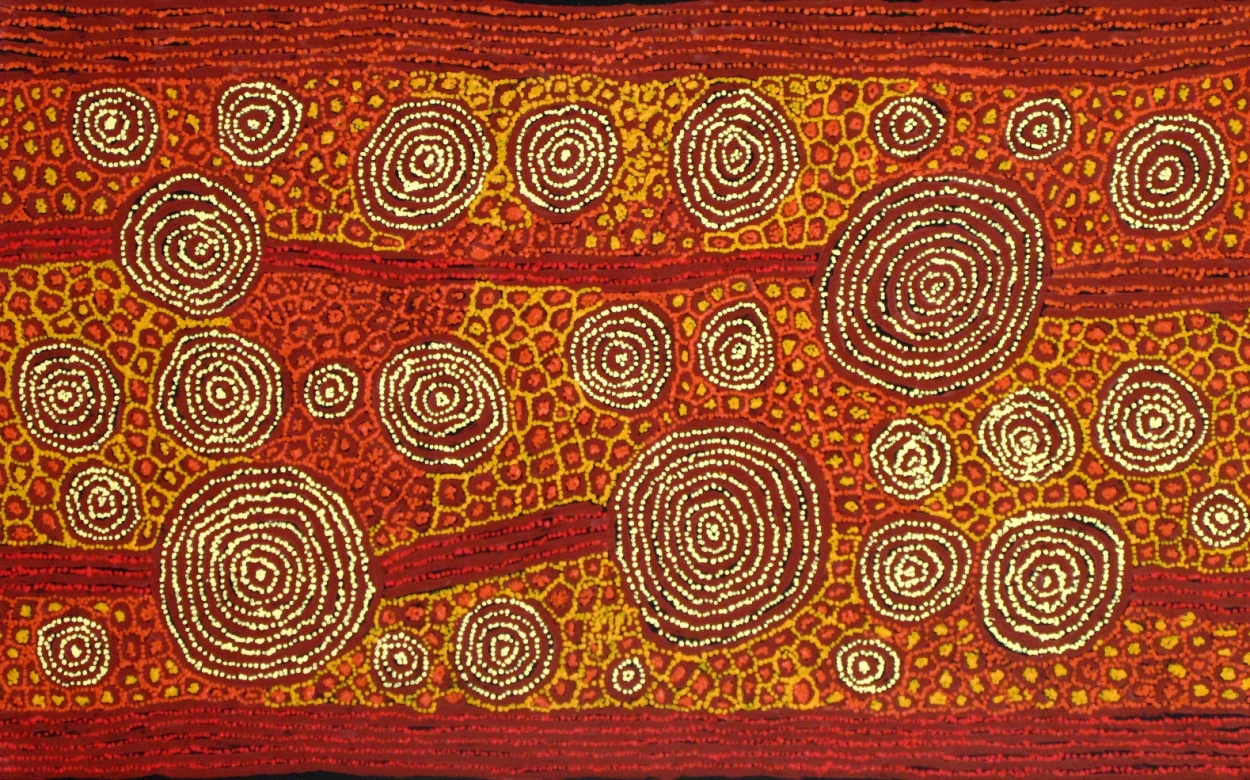

Abram draws on a very broad range of knowledge and practice of aboriginal groups in many parts of the world to suggest the scope, depth and brilliance of what has apparently been lost, but only apparently. They are not lost however exceptional it may be to even imagine recovering them.