A Review of Different: Gender Through the Eyes of a Primatologist

Once I’d finished reading it, I found I needed to really think hard to distil the main idea out of many ideas. For the text does have a complex structure: two genders, three species (humans, chimpanzees and bonobos), an obligation to “define” each of these things, that is, establish the central feature and set boundaries for them. Only after all that can the description of difference begin. And it is everywhere: difference between genders within a given species, difference between species in terms of the way gender plays out in each, difference between what scientifically-disciplined observation concludes and what casual received wisdom spouts forth at any given point. Plus there are differences over time, both in science and in received wisdoms.

So what was he really trying to do in this book? I think he is arguing in favour of gender ultimately referring to some “natural,” inevitable, fixed, given features that can be identified among viable groups of animals of a specie. Such a very general argument would hardly seem worth making, though, if it didn’t specifically oppose the general argument developed in the context of feminism, namely that gender — and it is very important to note that the contention is for gender in humans) is culturally constructed. I find it difficult to quite dismiss the suspicion that our primatologist set out to pick a fight. He defends gender scientifically as a fixed feature of highly evolved species, putting the weight of science (not to mention his own weight as a scientist and writer) behind it. Almost effortlessly, he turns the idea of gender being culturally constructed into fluffy girl talk. Did he really have to draw and defend the lines this way?

Many years ago (1964), Leroi-Gourhan sketched in a theory of human evolution that framed the human capacity for technics — for extending the animal’s physical and cognitive powers — it’s strength, perceptual acuity, memory, etc. — by adapting materials outside its own body to serve these functions. To oversimplify, it proposed that our technology IS our particular way of evolving. Given available technologies relevant to sexual or gender difference in humans, and given, further, the unthinkable complexity of even tracing, to say nothing of understanding how these quite recent possibilities are playing out among individuals and groups, it doesn’t really seem like a very good idea to insist on any kind of fixed, underlying biological reality.

Prof. de Waal’s book is highly readable and rich in examples of both very troubling and very heartening behaviour among our most closely-related primates. One incident — my very favourite in fact — wasn’t even about primates. Rather it was an instance of altruism involving an ostrich, living in a zoo, and recognising the plight of an orphaned baby elephant. It almost literally took the little one under its wing. The book tells of a range of behaviours, mainly among chimpanzees or bonobos, from vicious, lethal competition to subtle, selfless diplomacy. It makes for fascinating reading. It does not, I think, make a convincing case for or against any one understanding — including construction — of gender in humans.

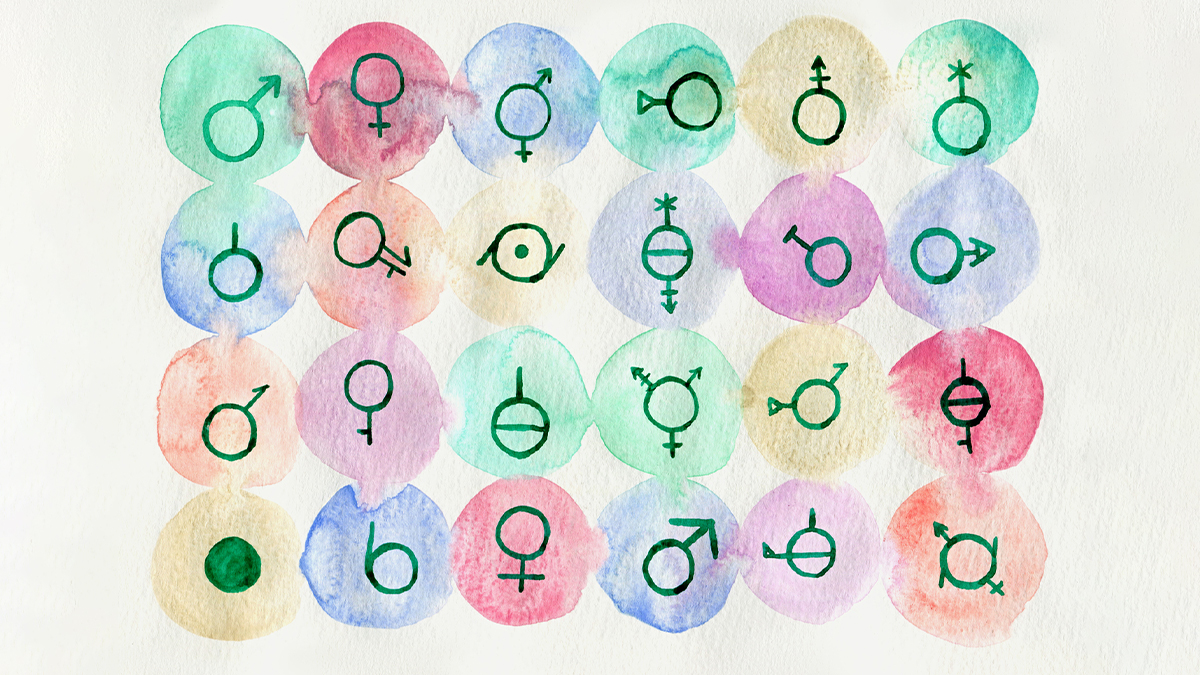

[This image is from The Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2020/11/transgender-gender-fluid-nonbinary-and-gender-nonconforming-employees-deserve-better-policies, accessed 11 May 2022.]

I enjoyed reading this, particularly in light of recent interactions in my very own primate family, as it were. Thank you! 🙂

Thanks, Katherine, apparently other primate species are looser about families than we tend to be — or have been since…hmmm, no idea actually.