Bateson’s Vision of Unity: Review of Biography

Gregory Bateson: The Legacy of a Scientist. A biography by David Lipset, Boston: Beacon Press, 1982.

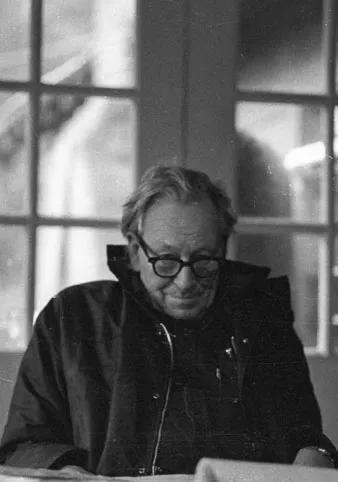

Gregory Bateson must surely have presented a daunting prospect to his biographer. Lipset takes us on an epic intellectual journey from genetics, Bateson’s father’s field (Gregory was named after Gregor Mendel), through the son’s own, always innovative work in the then-emerging field of anthropology, followed by a serious engagements with cybernetics, psychiatry, animal communication and more. He continues to be associated with terms he introduced, e.g. schismogensis and double-bind theory of schizophenia, among others. There are complexities in those aspects conventionally called “personal’ life as well:he was married three times, with a child from each marriage, all relationships strong enough to accommodate new circumstances, apparently without rancour. But the thread of the story lies in Bateson’s work: the issues and events that propelled substantial changes of context arose in his pursuit of a science that did not conflict with the human mind.

This book does not oversimplify: each of the very diverse segments in Bateson’s life is researched carefully and presented with a guiding idea of the life as a unified whole. And there are many, seemingly quite independent such segments: his youth and education in England, his anthropological field work, some of the best-known studies n New Guinea and in Bali with his first wife, Margaret Mead, his work with the US government communications during W.W.II, research in communications among patients in a prominent psychiatric hospital in California, study of communications among octopus, then dolphins, contributions to innumerable conferences and research projects.

I read this book very slowly, the reading interspersed with other reading, my curiosity about Bateson changing in response to many things, including what I learned in the book itself. When I finished, I went back to the beginning and read again about his family and early education, especially about the decisions that shaped him. I think it probably heightened my sense of a unity, or better, my sense of Bateson’s commitment to a unity. For a unity between nature — the object of natural science — and mind, the belief that ordered his life, seems always to have been there, even in the very early decisions that set his course — in a direction related to, but different from his family.

A reader gets a sense of an enormously gifted, superbly educated man — of whom much had always been expected — doing his best fulfil an obligation to humanity. One might well ask how this obligation came to be instilled, and wonder at its strength and tenacity. But given that such a question is unanswerable, it may be more appropriate to think of Bateson as a consummate teacher, someone who goes on teaching by means of his biography. He taught a vision of fundamental unity between us and nature, a relationship and responsibility we ignore at our own peril.